‘Crazy ideas’

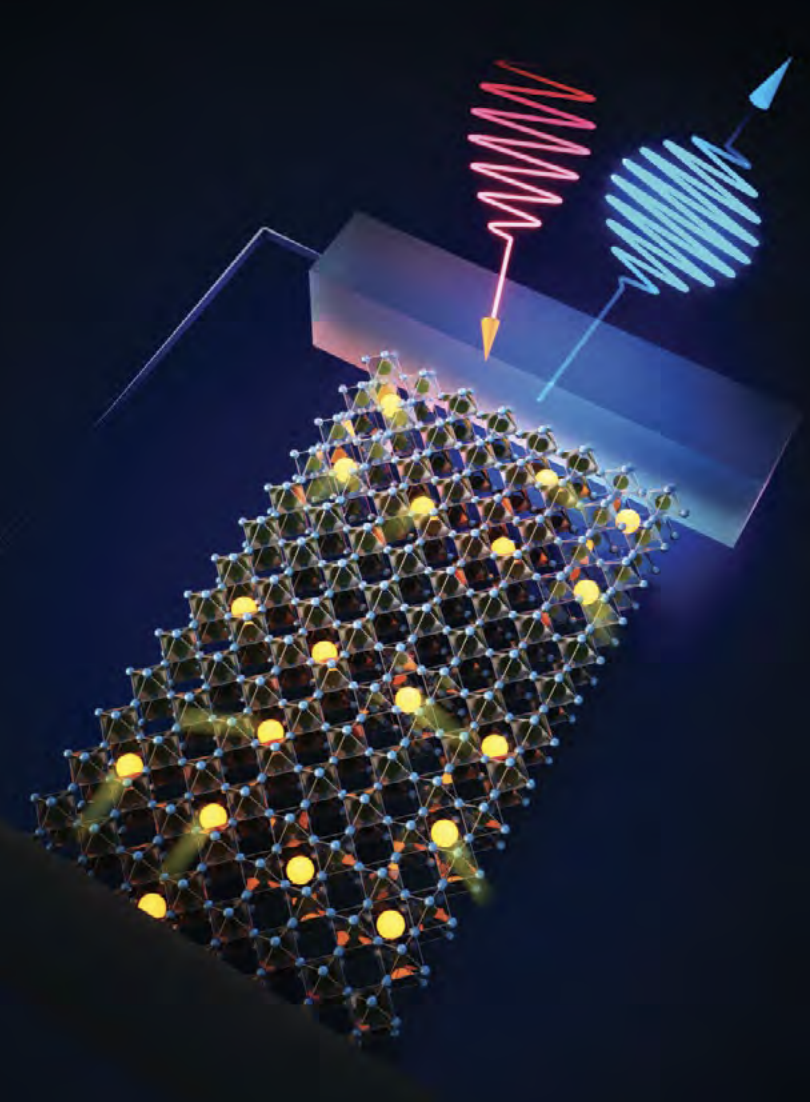

A diagram of X-rays (red wave) striking solid lithium battery materials and generating a measurable response (blue wave). Tod Pascal and colleagues model these systems to gain information about lithium-ion movement. (Image: Sasawat Jamnuch.)

When Tod Pascal was offered the Department of Energy Computational Science Graduate Fellowship in 2003, he was at a turning point. His undergraduate summer internship mentor, Caltech’s Bill Goddard, had encouraged him to apply for the fellowship and to Ph.D. programs around the country. But Goddard also offered Pascal freedom and intellectual support if he joined his group: “All those crazy ideas that you’ve been telling me that you want to work on? We could just work on them.”

Pascal chose Caltech, pursuing tough and fundamental questions about how molecules interact at nanoscale. It laid the foundation for a career that balances basic science with applications, chief among them designing new materials and, more recently, improving batteries. Graduate school’s core lesson, he says: It was OK to pursue ideas that don’t work out. “You’ll learn something, even if it is ‘don’t do that again.’”

Today, as an associate professor at University of California San Diego, he asks students in his own nanoengineering and chemical engineering research group to pursue fundamental questions, even ones that seem silly. The most interesting research directions in his group, he says, follow that process. “The genesis has been somebody asking a question, and I was like, actually, I don’t know. We should definitely go check it out.”

Pascal, who grew up on the island of Grenada, enjoyed chemistry, math and physics. Computing grew out of a shared interest with his father, who had spent a chunk of Pascal’s childhood studying computer science in the United States. When his father returned to Grenada, he brought his textbooks and the family’s first computer. “I had all his books on computing, and it became a source of connection for us,” Pascal recalls. His father challenged him to learn to code, starting with their eponymous programming language, Pascal. He soon learned C and Fortran and pushed himself to code his own computer game.

For his bachelor’s degree, Pascal enrolled in a specialized STEM program at Pennsylvania-based Lincoln University, which prides itself as the first degree-granting Historically Black College or University. He got his research start as a Fermilab summer intern. There, he helped David Ritchie sort through terabytes of high-energy accelerator data, seeking signals from subatomic particles. Ritchie had built a computational framework for the tasks, hundreds of thousands of lines of Perl code. Over that summer, Pascal was awed by the particle accelerator’s detectors and 100-foot rooms and realized that he could have a role in solving big science problems. “It cemented in my mind that I could marry all of these loves that I have: math, physics, chemistry and computing.”

During his Caltech Ph.D., Pascal used statistical physics and simulations to explore the mechanical, electrical and thermodynamic properties of graphite, graphene and common solvents.

As a postdoctoral researcher at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), he applied those concepts to studying energy storage, working with Yousung Jung in a department focused on energy, environment, water and sustainability. In one study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they showed how temperature and nanotube diameter affected whether water molecules could seep inside carbon nanotubes. “It’s all the things I found really, really cool and really, really hard,” he says. Spending a year and a half immersed in all things Korean was rewarding. “I got to go to cool temples and eat Korean food, which remains the great, great joy of my life.”

His KAIST research connected him with experimental chemist and current collaborator Richard Saykally at the University of California, Berkeley, who introduced him to computational physicist David Prendergast at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s Molecular Foundry. Pascal moved to Berkeley Lab in 2012 to work with Prendergast on interfacial phenomena and electronic structure theory.

Simulating X-ray spectroscopy expanded Pascal’s nanoscale toolkit.“Now we can come up with this computational framework to really look at nanoscale phenomena that directly connected to these amazing experiments being performed. This link is the key to our ability to not only apply our theories to real systems but, importantly, to use the wealth of data generated in the experiments to further refine our models.”

In 2017, he started his lab at UCSD. Some projects focus on fundamental molecular questions and basic science; others aim to predict smart materials’ structures and to design new battery materials. In a recent Nature Communications paper, they took a detailed look at the ion and electron interactions within layers of lithium-battery anodes and cathodes.

Even with the more applied research, the foundation of every project is fundamental questions, Pascal says. “Let’s say we’re working on an electrochemical system, like a battery. And we ask, okay, why does this work?” They’ll examine how electrons or ions move, what solvent molecules are doing and how they interact with the ions. Pascal remains motivated by testing out crazy ideas. And instead of going back to sleep when he wakes up at 4 a.m., he’ll often rise and run a quick simulation, and “it’s like, ‘okay, I’ve scratched that itch.’” Except now he’s pursuing those goals with hardworking, motivated students, he says, and they challenge each other with the goal of “creative solutions to some of these longstanding questions.”

Note: This article appears in the print version of the 2024 DEIXIS magazine.

About the Author

Sarah Webb is science communications manager at the Krell Institute. She’s managing editor of DEIXIS: The DOE CSGF Annual and producer-host of the podcast Science in Parallel. She holds a Ph.D. in chemistry, a bachelor’s degree in German and completed a Fulbright fellowship doing organic chemistry research in Germany.

You must be logged in to post a comment.