Justice adjustments

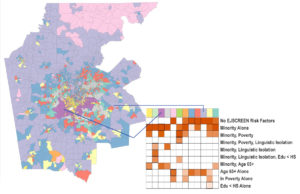

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) scientists created a geodemographic cluster for the Atlanta metropolitan area that identifies risk factors related to climate impacts. (Image: ORNL/DOE.)

As Earth’s climate crisis dramatically accelerates, a multidisciplinary team at Oak Ridge National Laboratory is focusing an environmental justice lens on a rapidly expanding big city: Atlanta.

“The idea has been around for a long time,” says Oak Ridge research scientist Christa Brelsford. “But the reach and scope of environmental justice-related research has really increased.”

Brelsford and other team members announced this past summer a “new capability to identify urban neighborhoods, down to the block and building level, that are most vulnerable to climate change.”

Using Atlanta for verification, the researchers combine statistical analyses of raw U.S. Census data with satellite imagery, manipulated via artificial intelligence, to “create a really systematic and empirically grounded risk profile,” Brelsford says.

The result is what the group labels a “synthetic population,” or what Brelsford calls a “data-based guess about the number of people in a census tract or block group who have some set of characteristics. For example, a person who is Black, poor and does not have access to a vehicle.”

Joe Tuccillo, a research scientist and human geography specialist in Brelsford’s group, leads the Urban Pop project, with a mission to simulate “synthetic populations to aid planning and decision-support objectives” in areas with environmental hazards.

For environmental justice modeling, Tuccillo uses tools that personalize raw census data collected from Atlanta neighborhoods, Brelsford says. That may divulge the number of people who are a particular race, have a certain income and don’t have access to a vehicle. But they don’t tell you about people who have all those characteristics at the same time.”

Meanwhile, colleague Taylor Hauser, a geospatial data analyst with Oak Ridge’s Built Environment Characterization Group, has developed special machine-learning techniques intended to glean insights from satellite-derived data.

Brelsford says that satellite imagery generally won’t reveal how big or tall a building is. And “neighborhoods are just fuzzy things.” Still, “everybody who lives in one knows that neighborhoods matter. It was our aspiration to use aerial imagery to guess about neighborhoods based on what we can observe.”

Synthesizing environmentally vulnerable populations and using machine learning on satellite data to suggest which urban structures those people occupy are unique tasks for a modeling exercise, Brelsford notes.

Her group’s goal is to formulate what she calls a “comprehensive risk profile” so “policymakers or emergency-response professionals can know in advance that these are the places where people who are physically or socially or demographically vulnerable are.”

Atlanta was picked because it’s a megalopolis that neighbors Oak Ridge’s host state, Tennessee, and because it could serve as “a microcosm of the Southern United States – an old city with all these interesting layers of how its urban environment has been built up over multiple decades.”

Of all the climate change impacts that news reports have dramatically documented, Brelsford’s Oak Ridge group exclusively zeroed-in on excessive urban heat because “that’s a clean and straightforward problem to model. Heat is really dangerous to the very young and very old, and if you lack the financial resources to leave or to adjust your indoor environment through air conditioning, then that’s a big risk factor.”

Heat risk is “also often the intersection of age, poverty and older buildings where heating and cooling aren’t managed as well.”

Brelsford, whose own training melded civil engineering with social science and environmental sustainability, says the concept of environmental justice picked up steam in the 1980s, targeting “the disproportionate exposure of Black communities to industrial pollutants and waste, and the exposure of poor kids to air pollution from traffic.”

More recently, climate modelers began evaluating the interaction of traffic-based air pollution with other climatic features. It’s been used to communicate that vulnerable communities – most often those who are poor and people of color – bear a disproportionate share of the harm from industrial waste, traffic, hazardous waste and urban heat.

In September, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan announced a new office “to infuse equity, civil rights and environmental justice into every single thing we do.”

He spoke in a North Carolina county where poor minority residents unsuccessfully opposed the establishment of a hazardous waste landfill 40 years ago.

“We in the national labs, we’re scientists,” Brelsford emphasized. “We don’t make policy.” But “I hope that work like ours provides useful information to people who do have the authority to make changes in our communities.”

Brelsford says that by 2050 about “two thirds of the world’s population is going to be in an urban environment, and most of the world’s population is already urban.”

For instance,21-county Greater Atlanta will grow from 6.3 to 8.6 million people by then, its regional commission reported. “So what, exactly, will that look like?” Brelsford asks. “Will it be a dense city with lots of skyscrapers in the middle? Or is it going to be a sort of rural to suburban sprawl? That’s a much harder question to answer.”

That local conditions are already “very different than it would have been with no buildings and no people,” she says, “is intuitively obvious.”

Models run on supercomputers will be necessary “to understand how more buildings and roads will influence atmosphere, water and temperature.”

About the Author

Monte Basgall is a freelance writer and former reporter for the Richmond Times-Dispatch, Miami Herald and Raleigh News & Observer. For 17 years he covered the basic sciences, engineering and environmental sciences at Duke University.