Getting a grip on the grid

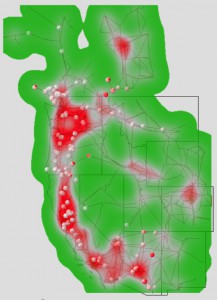

In this hypothetical scenario, red areas indicate vulnerable portions of the western North America power grid that network operators must address. Gray areas are causes for concern and green areas are safe. Overlaying risk-level data sets (here, 200 of them) allows operators to visualize the collective risk on the system.

When Zhenyu “Henry” Huang considers the grid of power sources and wires that supplies electricity to the United States, he doesn’t see a network so much as he sees a giant machine.

And it’s straining to keep up.

“The power grid is doing things today which it was not designed for,” says Huang, a senior research engineer in the Energy Technology Development Group at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, a Department of Energy facility.

“If something serious happens in the system, it can wipe out a whole region in a few seconds,” Huang says. “That’s why we want to think about how we can respond to those situations more quickly, and that’s why we want to look into high-performance computers to help us.”

Huang and fellow PNNL researchers are developing ways for powerful computers to quickly analyze which failures can combine to most threaten the grid. When multiple components break down, the consequences can be devastating, such as the massive blackout of the northeast United States and Ontario in 2003.

The risk of repeating such a giant failure is increasing as the power system copes with a list of major challenges – including rising demand on a grid that already operates near capacity.

Most of the problems stem from power systems’ high-wire balancing act. “You cannot store a large amount of power like you can store computers in a warehouse,” Huang says. Demand and production must always be roughly equal. Too much or too little generation can cause overloads, brownouts and blackouts.

The addition of renewable energy sources like wind and solar tests that balance. Passing clouds can make solar generation fluctuate; winds can suddenly accelerate or die, boosting or idling turbines. Power companies must quickly redistribute traditional generation to compensate.

Thinking fast

Power company employees and computers monitor the grid at large control centers. To cope with problems, they adjust generation and open or close lines and transformers to meet demand and reroute power.

That’s not good enough, Huang says. To avoid catastrophic incidents, utilities must be able to quickly analyze how failures affect the system.

A power system’s character completely changes over a period of hours, but usually does so slowly, says John Allemong, principal engineer for American Electric Power, an Ohio-based utility that owns the nation’s largest transmission system. However, “There are topological changes that occur fairly frequently,” he adds. “When those do occur it’s a good idea to get a handle on where you are fairly quickly. The ability to do so would be a plus.”